My Grandad, the Chindit

Introduction

Until the start of 2016, we knew very little about my Grandad’s time in the Second World War. He passed away in 1999 at the age of 83, and like a lot of veterans he didn’t really talk in detail about the war.

Towards the end of 2015, my dad sent away for Grandad’s army records, and we were surprised at what we got back – his movements throughout the war and his notification of release. We were proud to read:

Military conduct – Exemplary. A really good type of soldier, trustworthy, sober and cheerful, who always worked willingly. Saw active service in Burma 1944 and is strongly recommended for any employment entailing mechanical work, such as driving and maintaining a motor vehicle.

Despite having an interest in military history, I knew very little about the allied forces operations in the Far East – those of the ‘Forgotten Army’. But using my Grandad’s official army papers, plus other information, I’ve written this blog about the operations he would have likely been involved in and movements across India and Burma.

The boldest measures are the safest

James (Jim) Newton was born in December 1915.

In June 1939, three months before the outbreak of the Second World War, Jim married Ethel Bailey. They lived in Werneth, Oldham.

Home Service, 1940–1943

On the 13th June 1940, just a week after his and Ethel’s first wedding anniversary, Jim started his army service and was ‘called to colour’ for the Lancashire Fusiliers, Bury (1). He attained an A1 category during a medical at the British Military Hospital (BMH), Bury, and went on to join the Infantry Training Centre (ITC), Bury. On the 22nd June, Jim’s Territorial Army Record of Service papers were signed, and a few month later on the 29th November he was posted to 1/5 Lancashire Fusiliers, Bury at the rank of Private.

The following year, between 15th — 22nd August 1941, Jim was granted leave with reasonable absence (RA) at leave rate (Sudbury, Fusiliers) (2) and again on 7th — 16th October (Colchester, Fusiliers) (3). On the 1st November Jim was attached to 108 Regiment, Royal Armoured Corps (RAC), Barnard Castle, Fusiliers (4), and on the 25th November transferred to Kings Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) and posted to 13th Home Defence (HD) Battalion, Barnard Castle. On the 26th November Jim was recorded as ‘Taken on Strength’ (TOS), meaning that he was ready to be posted to a regular unit. A few days later on the 28th November Jim was posted to D Company from 108 Regiment, RAC, Little Marlow (5) as a Rifleman.

Between 7th — 15th January 1942 and again on 13th — 14th March, Jim was granted leave with RA at leave rate from the 30th Battalion KRRC, Little Marlow. On the 15th/16th June Jim was transferred to the 8th Battalion South Lancashire Regiment [1] as Rifleman, at Study Camp Park, Cambridgeshire (6). A few months later on 5th September Jim was classified as a Carrier Driver.

On the 6th January 1943 Jim transferred (PA)[2] to 4th East Lancashire Regiment, Long Melford (7) as a Private.

Jim’s Home Service came to an end on 16th June 1943, which in total lasted 3 years, 3 days.

Travelling to India, 1943

On the 17th June 1943, still in the UK, Jim proceeded on the draft serial no. RNWHA [3]. This was the start of his India service and soon after is when he embarked for India.

Based on Jim’s arrival date in Bombay (from his army records), it’s highly likely that he travelled in convoy WS31 [4]. The WS (Winston’s Specials) series of fast military convoys carried troops and equipment to the Middle East, India and occasionally the Far East. The series ran from August 1940 (WS.1) to August 1943 (WS.33) when it was replaced by the KMF series [5]. The WS series contained pre-war large liners which were converted to troop ships, usually maintaining a minimum cruising speed of 19+ knots.

WS31 convoy formed up at Oversay Island (Islay Scotland) on 21st June [6] along with convoy KMF17. KMF17, made up of eight ships, formed columns one to three, and WS31, made up of seven ships, made up columns four to six. Commodore of the joint convoys was the STRATHEDEN. When the convoys divided on 26th June, WS 31 retained the same formation, becoming columns 1 to 3. The convoy was escorted by cruiser UGANDA and 12 destroyers until it reached Gibraltar. At Gibraltar the destroyers were relieved by four other destroyers which escorted the convoy to Freetown where it arrived on the 4th July.

The convoy re-organised at Freetown and set sail on 6th July, and was joined by four more ships at Lagos. The convoy was escorted by various destroyers until it arrived at Capetown on 21st July. At Cape Town, a reduced convoy of just six ships then set sail on 26th July. Escort was provided by the cruiser DESPATCH and destroyers QUADRANT and REDOUBT from 26th July to 4th August, and the cruiser FROBISHER 4th to 13th August on which date the convoy arrived at Bombay.

It wasn’t all plain sailing, as RAF records show:

“On the 23rd June 1943, Flt Lt. J Wright and crew were escorting convoys WS31 and KMF17. A visual sighting was gained of three U-boats which dived on being attacked. Almost seven hours later the crew again visually sighted three U-boats. One dived whilst others opened fire. They then commenced diving. An attack was made using a 600lb bomb. No results were observed.” [7]

A few weeks later on the 11th July, Convoy Faith, which had set sail from Britain to West Africa, suffered heavy casualties when attacked by German long-range bombers [8].

The only ship of the WS31 convoy to depart from Liverpool and arrive at Bombay (without diverting elsewhere) was STRATHEDEN (P&O). It is therefore possible that Jim was on this ship, unless he changed ships at one of the ports en route.

On the 13th August, Jim disembarked in Bombay at GHQ British Base Reinforcement Camp. His records state Arrival 1 Company 1 Way (Ex UK). Army Class (A/C).

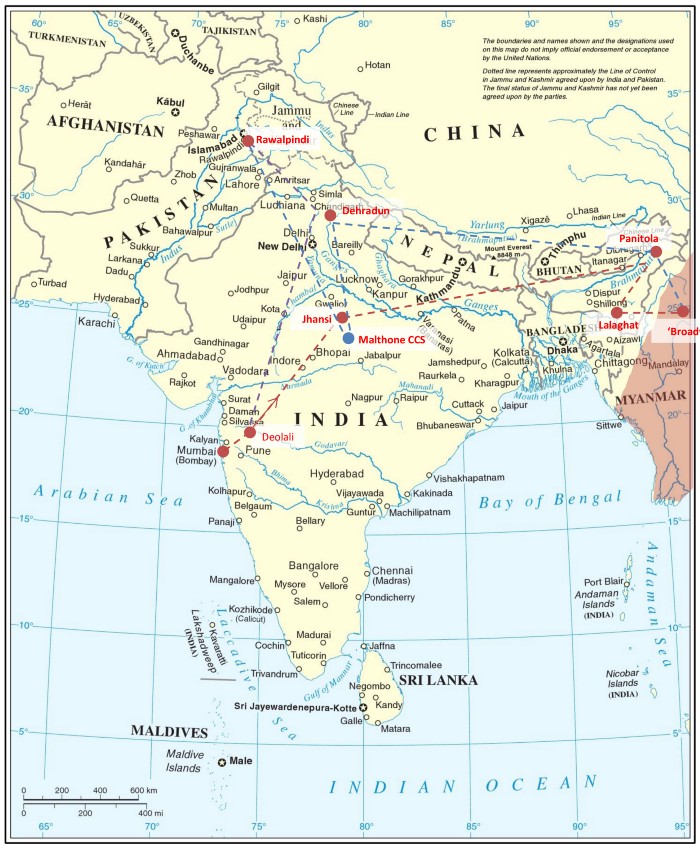

After arriving in India, it’s likely Jim then travelled by train to the Deolali Base Reinforcement Camp [11], as many others did [12]. This vast encampment was located roughly 100 miles north-east of Bombay and was formerly a Staff Training College. He may have arrived here on the 22nd August.

On the 15th September, Jim’s army records state he was S.O.S (struck off strength i.e. moved regiment) from the South Lancashire Regiment. He was placed on the South Lancashire Regiment’s X (IV) list (reinforcement awaiting posting to a unit). Jim was then transferred to the King’s Regiment (Liverpool), posted to 1st Battalion [13] with the rank of Private.

It’s known that Wingate drew reinforcements from wherever he could locate them for the 1944 Chindits operation [14];

“While we were there [at Deolali], a senior officer came to the camp looking for volunteers for a Special Force in Burma. It was a long-range penetration group (LRPG) named the Chindits, and it would operate 200 miles or so inside the Japanese lines. They said that this type of operation demanded more mature men who could handle the stresses of fighting inside the enemy’s lines” — Crawford Wishart on joining the 1st King’s (Liverpool) [15].

Such a change just before entering the concessional area certainly altered the course of the war for Jim. In Burma, the South Lancashire Regiment fought in the Arakan (1944), during the relief of Imphal and Kohima (1944) and the advance on Rangoon [16].

However, after joining the 1st King’s (Liverpool) Jim would have then travelled by train to a jungle camp near Jhansi in Central India and joined the rest of the Battalion. It’s in the forests of India where the Battalion learnt how to live and fight in the jungle [17];

“For months we trained in the jungles around Jhansi, marching many hundreds of miles with 60 lb. packs and engaging in army exercises designed to get us ready for Burma. The army provided tea, bread, beans, bacon, cigarettes, tobacco and other miscellaneous items. We shot deer and wild peacock for meat.” — Crawford Wishart, 1st King’s (Liverpool). [18]

When the training was completed, Jim would have made his way to Assam, India (near the Burma border) [19]. On the 21st January 1944 Jim entered the ‘Concessional Area’ (entitled to extra pay / concessions because he was stationed in a war area).

Operation Thursday, Burma, March 1944

Between the 1st January and 20th July 1944 there are no official army records of Jim’s whereabouts.

However, the following section has been written following Jim’s regiment — 1st Battalion King’s (Liverpool) Regiment — through the Burma campaign using online resources (including chindits.info, chindits.wordpress.com and ww2talk.com), and the books ‘Forgotten Voices of Burma’ by Julian Thompson and ‘War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944’ By Tony Redding. Other sources have been referenced for further reading. We also know from Jim’s personal accounts and his army records that he saw active service in Burma.

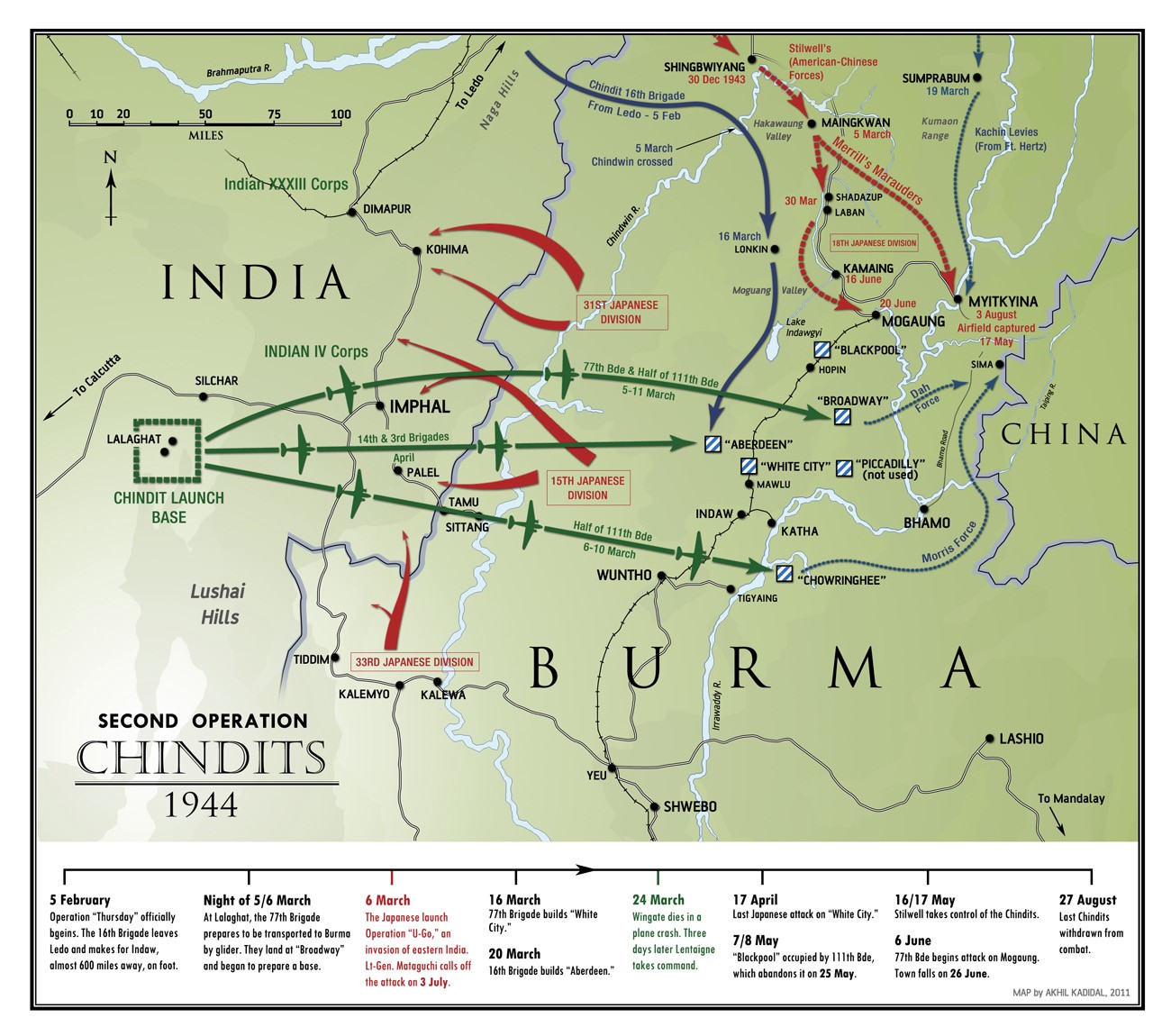

Being part of 1st King’s (Liverpool), Jim would have been part of the second Chindit force (also known as Special Force or the 3rd Indian Division, Long Range Penetration Groups), operating in Burma as part of Operation Thursday.

The Chindits were formed to put into effect Major General Orde Wingate’s newly developed guerrilla warfare tactic of long-range penetration, and the Chindits were trained to operate deep behind Japanese lines.

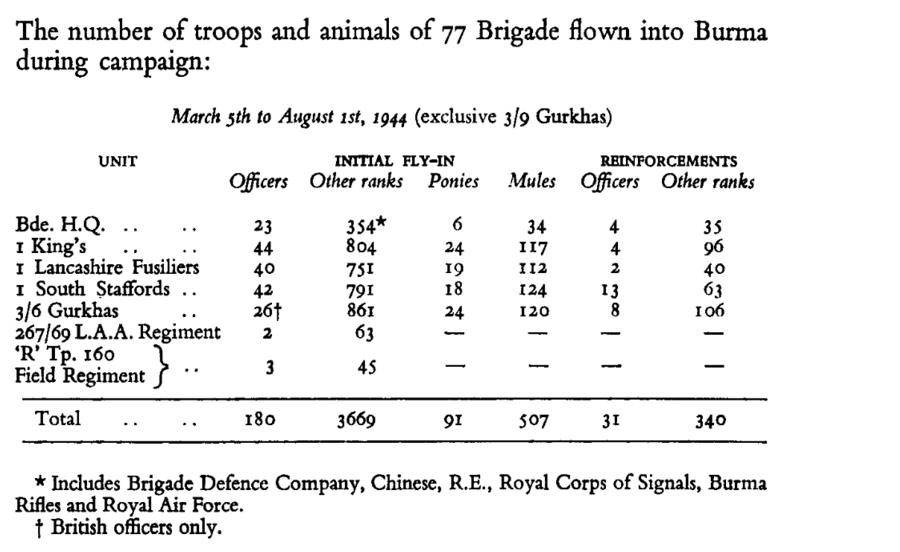

The second Chindit force was composed of six brigades, one of which being the 77th Brigade, made up of:

- 1st King’s (Liverpool) Regiment (onwards referred to as The Kings)

- 1st Lancashire Fusiliers

- 1st South Staffordshire

- 3/6th Gurkha Rifles

- 3/9th Gurkha Rifles

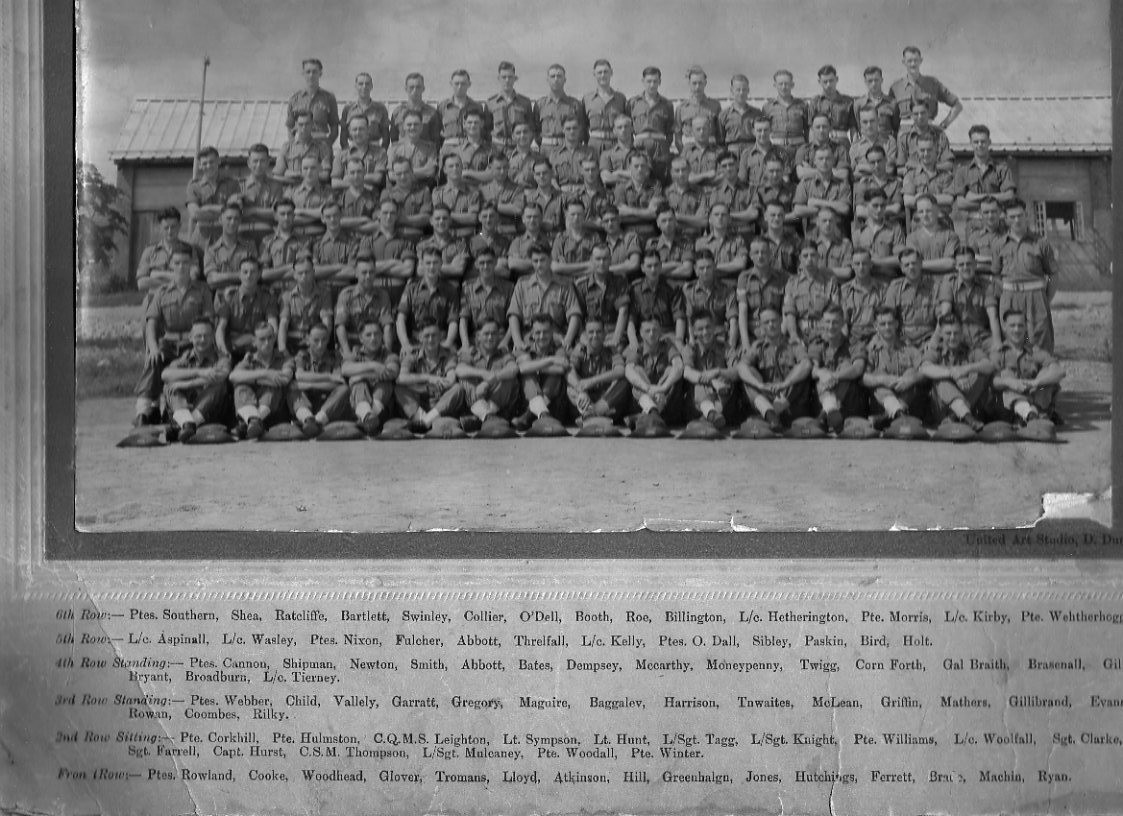

The Commander of the 77th Brigade was Brigadier J. M. Calvert DSO, and The Kings formed columns 81 and 82 of the brigade (there were eleven columns in total, plus air support). The commanding officer of columns 81 and 82 was Lieutenant Colonel Walter ‘Scottie’ Scott [20].

Each King’s column was made up of around 450 men and 56 mules to carry supplies and ammunition [21]. A column consisted of HQ, three or four Rifle Platoons, a Commando Platoon, a Recce Platoon and an attached Section of Burrifs [22]. Wingate envisaged that each column would be in the combat area for three months per operation, and be constantly on the move. Physical fitness was therefore vital.

The objective of Operation Thursday would be to cut the supply lines of the Japanese forces facing British, American and Chinese forces in north Burma, and cut the communication lines to the forces facing Stilwell’s advance.

As part of Operation Thursday, the initial Chindit move centred on 16th, 77th and 111th Brigades. The aim was to fly in a force of 10,000 men, 1,000 mules, equipment and supplies into clearings in the heart of Burma, behind enemy lines, and from there attack road, rail and river traffic in the area. This type of operation had never been attempted before.

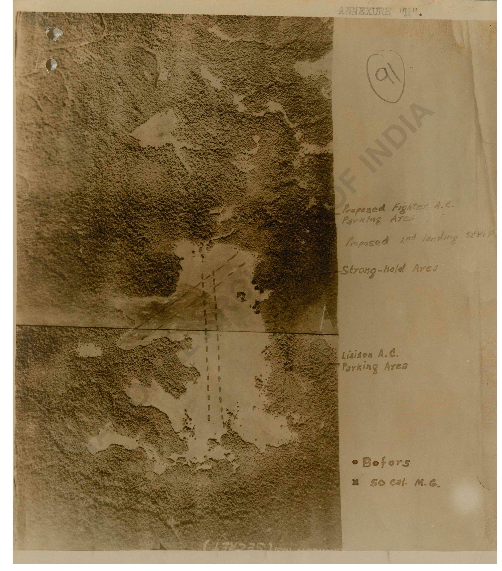

Three sites were selected for the initial landing grounds and were given the code names Piccadilly, Broadway and Chowringhee. These landing sites had been chosen in inaccessible areas to avoid contact with Japanese ground troops and all sorties were to be flown at night to avoid Japanese aircrafts. The plan was for a first wave of gliders to land troops to secure the site. A second wave would land more troops and American engineers to construct an airstrip so that C47 Dakotas could bring in the remaining troops and equipment [23].

“The plan was that my 81 Column would land at Piccadilly, and 82 some thirty miles to the north in another clearing known as Broadway. The role of these column was to clear the area and hold it so that bulldozers could be flown in to construct airstrips.” — Lieutenant Colonel Walter ‘Scottie’ Scott. [24]

However, just before launch Piccadilly was withdrawn from the plans and it was decided that the initial landings would be at Broadway.

On the night of the 5th March the first wave of gliders flew into Broadway. The initial glider landings did not go well. Aerial photographs had failed to show ditches and two trees on the landing area at Broadway and these had caused several of the gliders to crash on landing and were now blocking the path for further gliders; 30 men were killed in the landing and a further 28 wounded. However, on the first night, 35 gliders managed to land successfully and by dawn 400 men were ready for action in Broadway. The next morning a runway was cleared for Dakotas to land, and over the next six nights, 579 Dakota sorties flew into Broadway, successfully bringing in 77th Brigade and two battalions from 111th Brigade. In all, some 18,000 troops with their animal transport “had been inserted into the enemies guts” (as Wingate described it), 200/150 miles behind the main Japanese front in Assam.

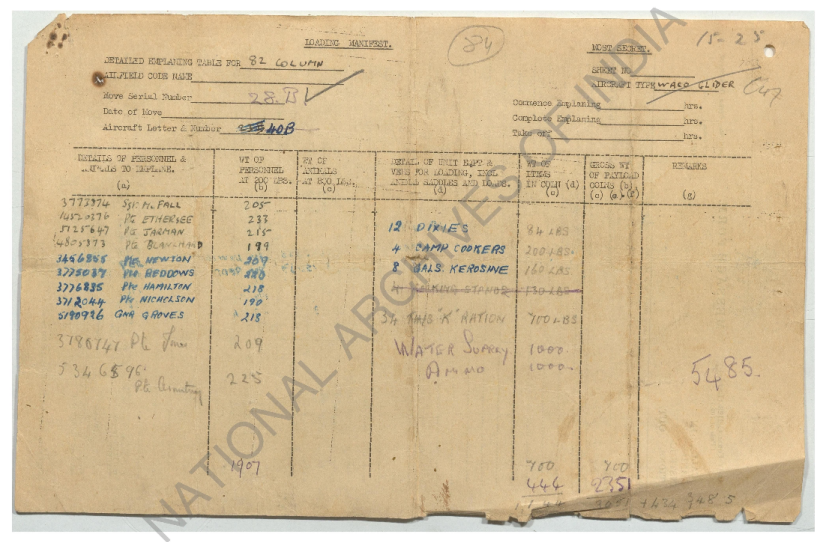

In early 2025, we found the loading manifests for Operation Thursday from the National Archives of India. With thanks to members of the WW2Talk forum, we found the manifest that listed James.

It confirmed that James was part of the 82nd column, with the move serial number 28B. He flew in a C47, also known as a Dakota, with the aircraft letter and number 40B (changed from a Waco Glider 28B).

The manifest includes the weight of the personnel (soldier, with pack, rifle, etc.). James’ total weight was 209 LBS (which is 14 stone and 13 pounds).

On his plane were:

- 377387 Sgt McFall. Stephen Donald. M.M.

- 14320376 Pte Ethersee. George Edward.

- 3725647 Pte Jarman.

- 4805873 Pte Blanchard.

- 3456855 Pte Newton. James

- 3775037 Pte Beddows.

- 3776835 Pte Hamilton. Herbert Kitchen

- 3712044 Pte Nicholson. H. (wounded 15/07/1944)

- 5190926 Gnr Groves.

- 3780747 Pte Jones. J.H. (wounded 23/06/1944)

- 5346596 Pte Armstrong. W

- 12 Dixies 84 LBS

- 4 Camp Cookers 200 LBS

- 8 Gals Kerosine 160 LBS

- 34 Tins “K” Ration 700 LBS

- Water Supply 1,000

- Ammo 1,000

Again, thanks to members from the WW2Talk forum we know that James’ sergeant, Sergeant Stephen Donald McFall 3773874, of the 77th Indian Infantry (Division - 3rd Indian, Unit - 1st Bn The King's (Liverpool) Regiment), was given a recommendation for a Military Medal on 6th July 1944 (see appendix for full recommendation).

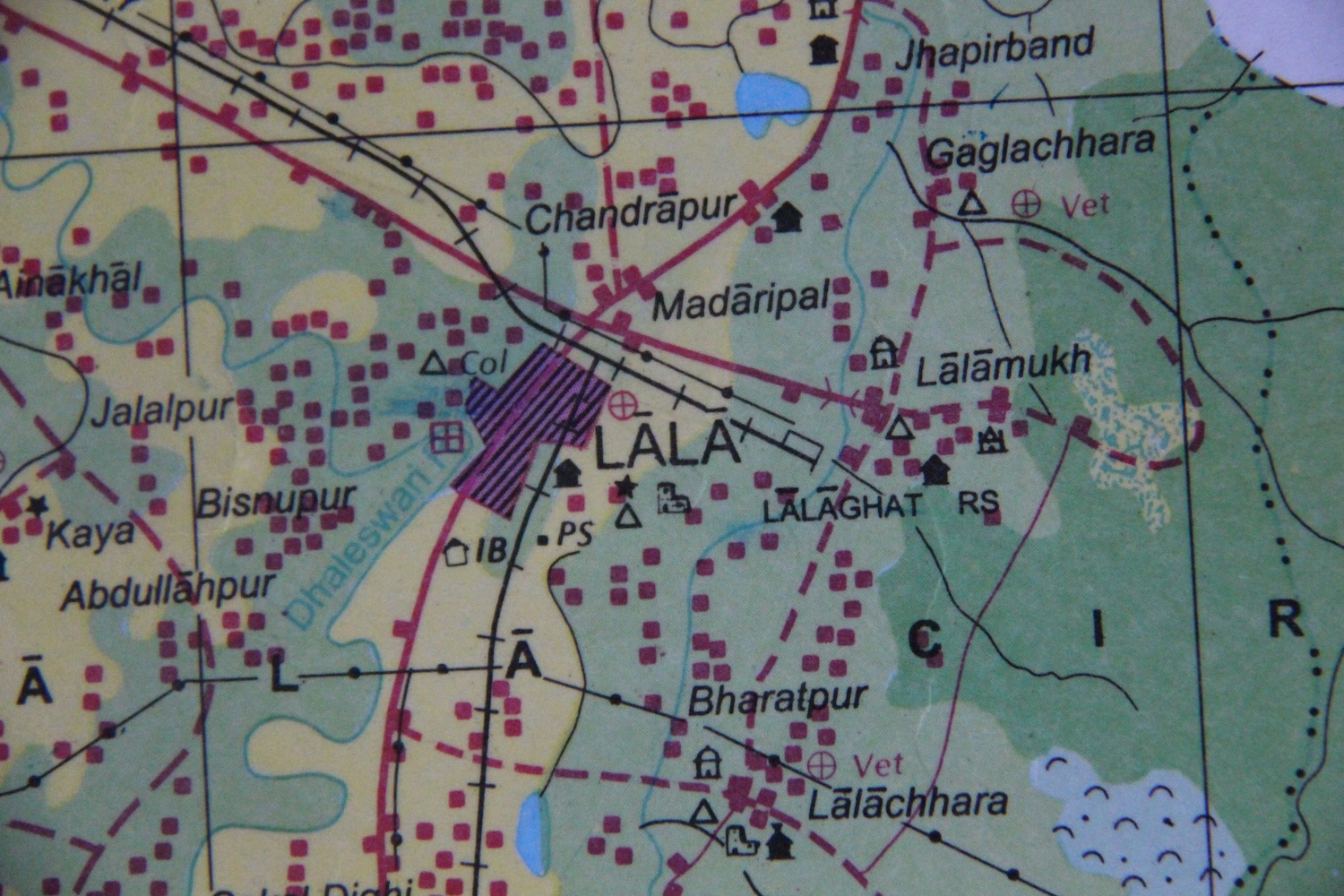

Additionally, in early 2025 I spoke to a member of TripAdvisor whose father had fought in Burma, and who had travelled to East India in 2015 to find the launch base of the gliders and aircraft, and to visit his father’s grave in Taukkyan Cemetery outside Rangoon. After talking to locals, he described the launch location as being “just a little further east of the point where the train line ends at Lalaghat, itself just east of Lala. I believe it to be behind the copse of trees that are shown on the map which the 'h' of Lalamukh is sitting on. The airstrip was never more than a stretch of flat earth without use of materials so I doubt there will be any trace of it today”.

Back to 1944... Wingate now had three brigades in Burma, and Broadway was rapidly developed into a powerful air base with firmly constructed defences. Within days of landing, Chindit columns were marching off along jungle paths to establish themselves in the region [25]. The columns would strike against the railway, road and river systems used by the Japanese army operating against Stilwell’s Chinese-American forces approaching from the north.

Initially, The King’s 81 and 82 columns operated as floaters beyond the perimeter of Broadway. Column 81 was in the Bhamo area, and column 82 made for Kaukkwe valley [26];

“We didn’t go looking for the Japanese. Our job was to blow up bridges and railways, and stop supplies getting through to the Japanese Army. At night we would usually camp near a stream which we would use in three sections, one for our drinking water, one for the animals, and another for washing. We just dug a trench for latrines.” — Crawford Wishart, 1st King’s (Liverpool) [27].

The first ground challenge to Broadway from the Japanese began on 26th March, when column 82 floater patrol ambushed a 150-strong Japanese force. During the morning of 29th March the Japanese were digging in north of the perimeter. Column 82 was ordered to return to assist in the defence of the stronghold. Three days of hard fighting at Broadway concluded with a counterattack by the Gurkhas (9 GR) and 82 column on 31st March. The Japanese pulled back from the north of Broadway, but started to probe at the south;

“We did not take any prisoners because we were always on the move and we could never trust the Japs anyway. We got our food and other supplies dropped to us by plane every three days, using a clearing in the jungle.” — Crawford Wishart, 1st King’s (Liverpool) [28].

While columns 81 and 82 stayed local to Broadway, the rest of 77th and 111th Brigade probed further into the jungle, setting up new strongholds including ‘White City’ and ‘Aberdeen’.

Operation Thursday was successfully over and Churchill sent Wingate a telegram congratulating him and the Chindits on their outstanding success. This was the largest Allied airborne operation ever conducted until D-Day.

However, tragedy soon hit. On 24th March Wingate flew into Broadway in a B-25 Mitchell bomber from 1st Air Commandos. From there he visited the White City and Aberdeen Strongholds. After returning to Broadway he flew on to Imphal to meet Air Marshall Baldwin and from there he set off back to Lalaghat. Wingate’s plane crashed on the return journey in the hills around Bishenpur. All on board were killed including a number of war correspondents [29].

Winston Churchill said of Wingate after his death:

“There was a man of genius who might well have become also a man of destiny. He has gone, but his spirit lives on….”

But perhaps the best euological words came from his opposition, the famed Japanese Lt-General Renya Mataguchi, who upon hearing the news of Wingate’s death after the war said;

“I realised what a loss this was to the British Army and said a prayer for the soul of this man in whom I had found my match.” [30]

Blackpool, Burma, 1944

After Wingate’s death, command of the Chindits was given to Brigadier Lentaigne, the commander of 111th Brigade, and on the 17th May to General Stilwell, U.S. Army. This marked a bold and offensive change in both the Chindit’s strategy and tactics. Wingate’s original plans were now being discarded. The Chindits would now be used as normal infantry, even though they were not equipped or trained to do so. They were used to assault strong Japanese positions without the normal armour and artillery support and heavy casualties resulted.

Orders were given to the brigades to abandon their strongholds and move north to set up a new stronghold and block near Hopin, codenamed ‘Blackpool’. 111th Brigade was to establish this new block with 14th and 77th Brigades acting as mobile columns nearby [31].

At Blackpool, 111th presence was noted from the start (7th May) [32]. The Japanese mounted nightly raids, giving the defenders little rest; having to repel the Japanese at night and work all day on the defences or unloading planes when they arrived. Whilst the stronghold was able to receive a complement of artillery and anti-aircraft guns it never constructed the heavily timbered dugouts or the mined, multiple wired, outer defences that were the characteristic of White City.

At this time, King’s 81 and 82 columns were still at Broadway and had been acting as floaters once again, patrolling around Broadway mainly in the Kaukkwe Valley. [33] Reinforcements were needed at Blackpool, and The King’s columns 81 and 82 left Broadway to march to Blackpool to provide this. Between the 8th — 25th May, The Kings were officially a part of 111th Brigade.

On the 19th May, The Kings were ambushed en route to Blackpool (at Pinbaw) and the columns became split;

“We were ambushed and all hell broke loose. Mules were dashing around throwing their loads, screaming in terror, grenades exploding, machine-gun and rifle fire, and the worse of all, screaming of the wounded and dying” [34].

Many men were wounded or killed, with 400 or so leaving the march from 82 column (commanded by Major Richard Gaitley) and headed away to the east towards Mogaung [35]. The 140 or so separated men made a prodigious march up 4,000 feet and down 4,000 feet in wet weather, covering in two days over 25 miles, often up to their knees with mud [36]. They joined the 1st Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers at Tingmongyang and was committed to the battle of Mogaung from 1st — 26th June.

However, the main bulk of 82 column reached Blackpool on 20th May, joining 81 column, to be followed a few days later by 3rd/9th Gurkha Battalion (also sent from Broadway) [37]. Based on some later dates in Jim’s army records, and the rule of probability, it’s more likely he made it to Blackpool.

The men of 82 column who made it to Blackpool dug in on the forward slope overlooking the airstrip and its collection of wrecked Dakotas. Two or three men occupied each trench; the Japanese attacked repeatedly:

“They got through the wire on a regular basis, but never in any strength. We had Vickers guns on fixed lines of fire. The perimeter defences were quite strong but, at this point, the Japanese were only probing for weak spots.”

The men got no peace.

“We were supposed to be a floater column, but all hell was going at Blackpool. Soon, everyone was needed inside the perimeter”. [38]

Even with The King’s arrival, all units at Blackpool were much under strength, due to previous engagements, with the consequence that there were insufficient numbers to form mobile columns to attack Japanese units and artillery. The onset of the Monsoon rains had also turned Blackpool into a sea of mud [39]. They became isolated and overwhelmed.

By the 23rd May, with mounting casualties, shortage of ammunition, ever-increasing Japanese artillery bombardment, encroachment of defences by attacking Japanese troops and with sniper fire from surrounding hills, abandonment of the stronghold was ordered. So began the withdrawal up the jungle covered hills, with The Kings forming the rear guard;

“In the closing minutes we were fighting hand-to-hand with the Japs in the block” [40].

Half way over the mountains the Brigade were met by West African troops who assisted them over the hills and into the Indawgi Lake valley. The sorely tired command trekked to Mokso Sakan with little or no food. The plan was to withdraw from around Indawgyi Lake’s southern shore.

“They were a pitiful sight, ragged, tired, dazed, they staggered up the track. The worst cases followed at the end. Two platoons of Gurkhas protected their rear. The force consisted of the remnants of the following columns: 48, 41, 46, 81, 82, 90 and 93. There wasn’t much we could do for them except carry stretcher cases, for we had no food to give them. That night our request for an air drop was accepted for 08:00 on the 27th May.” — Intelligence Officer Lieutenant Bill Cornish [41].

By 30th May work was progressing to establish a flying boat based to evacuate the sick and wounded from Indawgyi Lake. Around 350 men required evacuation, and their numbers increased at an alarming rate following the two weeks of Monsoon rain (malaria cases spiralled) and with little or no food. The men were also short of arms and ammunition. Blackpool’s survivors were weak and debilitated; most were ill and traumatised by their experiences. The men still fit enough to fight were re-equipped and reorganised. The King’s 81 and 82 Columns became a composite 81 column [42].

Final Battles, Burma, 1944

On 8th June, the (now understrength) 111th Brigade were ordered to move on Mogaung from the west, including the remaining King’s led by Corporal Fred Holliday. The 111th brigade moved north-east and operated in the Pahok-Sahmaw area, destroying dumps and blocking enemy position. They were soon ordered north to the hills of east Lakhren and west of Mogaung.

From 8th — 18th July, 111th Brigade took part in hard fighting around Point 2171, a spur above Taungni, overlooking the Mogaung river. After the two week battle, on the 20th July the Gurkhas led the advance and took Point 2171 [43]. Conditions at the top of Point 2171 were appalling, and there was great bitterness when the victors were ordered to pull back. The Japanese returned to Point 2171 in early July. Point 2171 was 111th brigade’s last major objective.

On the 17th July an inspection of the Indian 111th Infantry Brigade found that only 118 were completely fit for active service; many of the remaining about 2,200 men suffered from malaria, foot rot, septic sores, typhus, or other ailments related to the Burma jungles. It is possible, based on Jim’s records and his admittance to a combined military hospital (CMH) on the 20th July, he was withdrawn at this point.

A few days later, special force commander Joe Lentaigne told Sitwell that 111th Brigade was being withdrawn on his own decision, regardless of consequences. Over 2,000 unfit survivors were withdrawn to Kamaing and the remaining 119 were formally released 10 days later. Full withdrawal of 111th took place between 27th July — 1st August.

On their return, one in two men were admitted to hospital and nearly all required rest and a special diet. They had fought long past the prescribed period set by Wingate, long past the limits of endurance and even in their final hours had shown gallantry of the highest kind. The two Chindit expeditions extended the boundaries of human endurance. The Chindits suffered slow starvation and exposure to dysentery, malaria, typhus and a catalogue of other diseases. They endured the intense mental strain of living and fighting under the jungle canopy, with the ever-present threat of ambush or simply ‘bumping’ the enemy. The King’s lost 97 dead during the 2nd Chindits operation, with almost all the remainder being wounded or suffering from medical conditions. However, The King’s were the only Regiment to be awarded both Chindits 1943 and Chindits 1944 as Battle Honours.

“Throughout this operation, the 1 Bn The Kings (Liverpool) Regt. showed the greatest readiness to accept losses and sacrifices in order to make the operation a success. Their cheerfulness in the face of apparent disaster is due in a large measure to the personal example and character of their Commanding Officer.” — Transcript of Distinguished Service Order Citation for Major (temp Lt-Col) W.P. Scott. [44]

India, 1944

On the 20th July 1944, Jim was posted to X (ii) list (evacuated on medical grounds beyond the regimental aid post [45]) and was admitted to Combined Military Hospital (CMH) Panitola, Assam, India, close to the Burma border. Two days later on the 22nd July he was discharged from CMH Panitola, and on the 27th July, returned from the concessional area (but still recorded as ‘in the field’).

“When we came out of Burma we again returned to Assam. We had been in for over five months and not once had most of us had our uniforms off. We were filthy, stinky, tired and hungry and, for once, the British Army looked after us. Endless showers, new uniforms and boots, good food that we had trouble keeping down and medical treatment for jungle sores and foot rot.” — Crawford Wishart, 1st King’s (Liverpool) [46].

On the 1st August, Jim reported to the Unit Depot (1st Battalion, Kings), which is likely to be the northern Indian town of Dehra Dun. The Battalion were based at the Clement Town Cantonment for a period of recuperation. On the 4th August Jim is recorded as ‘Adm. to P W Camp Hospital, C Town, to X (ii) C list’. There were a number of POW camps at Dehra Dun [47], mostly for military prisoners. During this period, the POW camp hospitals were used as overflows for the Chindits, and it’s possible that Jim was sent to one during his recuperation period.

On the 7th August the Indian 36th Division became the last Chindit formation to engage in combat in Burma [48]. The last Chindits withdrew from combat on 27th August [49]. A month later on the 2nd September Jim’s records state: Service abroad 1/78 ‘A/S’ Gp 26C.

On the 17th October 1944, Jim was discharged from hospital, probably still at Dehra Dun, to 1st Battalion, Kings. It’s possible he then stayed at Dehra Dun for a few more months to recuperate.

15th (British) Parachute Battalion, India, 1945–1946

On the 21st February 1945, Jim was admitted to the Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) in Malthone, India and posted to the X (ii) list. A few weeks later, on the 3rd March, he was discharged from CSS Malthone to 1st Battalion, Kings.

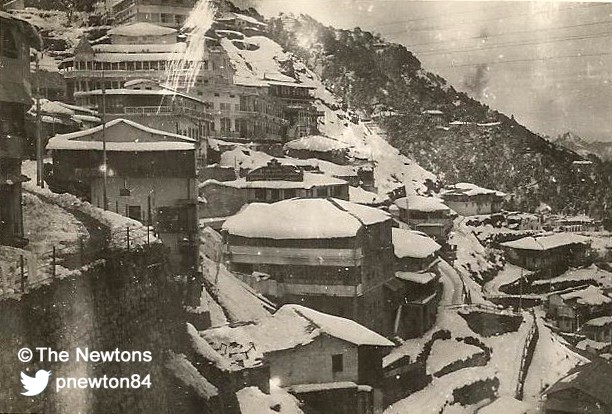

A new battalion, the 15th (British) Parachute Battalion, was formed at Malthone in 1945 from a nucleus of volunteers from the 1st Battalion The King’s Regiment which had previously had a role with the Chindits operations (made up to strength by a draft from 13th Kings before that Battalion was disbanded [50]). It belonged to the 77th Indian Brigade, part of the 44th Indian Airborne Division [51]. This new unit was preparing for the challenges of re-taking Malaya from the Japanese. Parachute training commenced at Chaklala, near Rawalpindi, from March [52].

“I volunteered to join the Parachute Regiment and was posted to Rawalpindi, which was the training centre at that time. There followed 7–8 days of intensive ground training in which we learnt about the parachute, how it worked, how to use it and more importantly, how to land safely. I think more time was spent on landing technique than any other aspect of the parachute, to ensure as far as possible, a safe landing on the ground.

The second week started with two acclimatisation flights, to get us used to flying and to try and minimise the air sickness problem. Carried out in Douglas Dakotas, mostly over some of the foothills of the Himalayas, these were pretty rough flights. The RAF were responsible for the entire training program and our instructors were two flight sergeants.” [53]

On the 1st May, Jim was admitted to BMH Rawalpindi, India to the X(ii) list, and was discharged two weeks later on the 15th May.

On the 31st May, Jim was admitted to CMH Cl Town, still on X (ii) list, and later transferred to CMH Dehra Dun, India on 25th June. Jim was discharged from CMH Dehra Dun to 1st Battalion, Kings three weeks later on 14th July. It’s likely that Jim’s health troubles from his time in Burma were still an issue. We know from personal accounts that Jim had malaria whilst in the jungles of Burma, and had part of his stomach removed when back in England – he was troubled by stomach problems for the rest of his life.

On 6th August 1945, an American B-29 bomber dropped the world’s first deployed atomic bomb over the Japanese city of Hiroshima, marking the start of the end of World War Two.

Returning to the UK, 1946

On the 2nd February 1946 Jim was en route back to the UK, with it being recorded: To Homeward Bound Trooping Depot (HBTD) for refial UK. (Class A release) SOS Unit to X(8)a [54], India.

“At the end of 1945 quite a number of officers and N.C.Os were sent home, and the night before their departure we had a party and quite some party that was! I was sent to a place called Dodali just outside Bombay to wait for a ship to take us home to England. It was a camp of just tents and beds and nothing else, no amusements, shops, cinemas of any kind. I had often heard of people being doolali (out of their mind) and now I knew why because we waited six weeks for a troopship to take us home and we nearly went out of our minds.” [55]

However, Jim’s wait wasn’t too long and on the 11th February he embarked at Bombay for return to the UK, this time sailing across the Indian Ocean, through the Suez Canal and across the Mediterranean.

During the journey home on the 19th February Jim received his notification of impending release from The King’s:

Military conduct ‘Exemplary’.

Testimonial: ‘A really good type of soldier, trustworthy, sober and cheerful, who always worked willingly. Saw active service in Burma 1944 and is strongly recommended for any employment entailing mechanical work, such as driving and maintaining a motor vehicle.’

Army education: ‘Unit cobbling, 4 weeks, 30 hours, achievement good.’

Jim arrived back to the UK on 1st March.

“The English Channel was littered with tropical gear thrown overboard by happy soldiers”. [56]

Once back in the UK, Jim was posted to Y list (entitled to 7 days home leave because in hospital for more than 21 days), Class A release. This was the end of his India service, which in total lasted 2 years, 258 days. Jim’s home service started on 2nd March and ended 90 days later on 30th May.

On 31st May Jim was eased to Class Z (T), Royal Army Reserve (Class A release) Territorials, and returned home to Chadderton (a different address to where he and Ethel lived at the start of the war).

In 1947, the 15th Battalion, The Parachute Regiment, was converted back to the 1st King’s (Liverpool) Regiment [57].

On 6th September 1948, Jim was awarded the stars, clasps, medals:

- 1939–45 Star

- War Medal

- Burma Star

- Defence Medal

Jim’s son (my dad), Stephen, was born March 1950.

On the 30th June 1959, Jim was discharged from Reserve Liability: Navy, Army and Air Forces Reserve Act 1959.

Colourising my Grandad's photos

Read my other blog where I have colourised some of my Grandad's photos from Burma and India.

Further reading and diaries

Further reading:

For more on what the 77th and 111th brigades had to endure in Burma, the book ‘War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944’ By Tony Redding is a good summary (view on Amazon here > https://amzn.to/3bUskhZ).

‘The Road Past Mandalay’ by John Masters (111th) and ‘Prisoners of Hope’ by Michael Calvert (77th) also give a unique insight into the operation.

Richard Rhodes James’ ‘Chindit’ has also been recommended as an essential read.

‘To Blazes With glory…’ by Joe Milner tells the story of a group of 1st Battalion King’s (Liverpool) soldiers.

Further listening:

An interview with Walter Purcell ‘Scottie’ Scott can be heard on the Imperial War Museum website where he recollects of operations commanding 1st King’s during Second Chindit Expedition, 1944: www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80012086.

An interview with James Michael ‘Mad Mike’ Calvert can be listened to at www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80009725.

Further watching:

In 2016, Channel 4 aired a programme called ‘Messages Home: Lost Films of the British Army’. This was based on a piece of word by Manchester Metropolitan University called ‘Calling Blighty’. The Calling Blighty series of short films, made in 1944–46, shows servicemen (and a very few women) in the Far East recording a message to be seen by their families and friends in local cinemas back home. It’s worth a browse at nwfa.mmu.ac.uk/blighty/index.php.

War diaries of interest (not a complete list, held at The National Archives):

WO 172/4445–111th Indian Infantry Brigade: H.Q. 1944 Jan — Aug

WO 172/4436–77th Indian Infantry Brigade: H.Q., 1944 Mar — July, Oct — Dec

WO 172/2515–1 King’s Regiment (Liverpool), 1943 Jan — Mar

WO 172/4885–1 King’s Regiment (Liverpool), 1944 Nov — Dec

WO 172/7637–1 King’s Regiment (Liverpool), 1945 Jan, Feb, May — Dec

Advice from a WW2 forum — “The 1st King’s War diary for 1945 is a very large document, but from flicking through it at various times, it has some useful information on the unit’s re-organisation and also later on in the year, details of some of the men’s repatriation to the United Kingdom. I have never been able to find a diary for the period of January/October 1944, I imagine they had been swallowed up into the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade by then and appeared in these files and possibly in the 111th Brigade too”.

War diaries can be searched for from www.nationalarchives.gov.uk, but very few are available online. Most can be read at The National Archives at Kew.

References

[1] The 8th Battalion South Lancashire Regiment was disbanded in 1943

[2] This may either stand for Pay and Allowances or Public Affairs, http://ww2talk.com/forums/topic/9614-abbreviations accessed 12 Jan 2016

[3] Seems to be a random set of characters when troops moved, http://ww2talk.com/forums/topic/50973-draft-recognition-codes/ accessed 12 Jan 2016

[4] The convoy arrived in Bombay on 13th August 1943, the same date as in Jim’s army records, and is the only troop convoy to arrive in Bombay +/- 5 days of that date.

[5] http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/ws/index.html?home.htm~wsmain, accessed 5 Jan 2016

[6] http://www.naval-history.net/xAH-WSConvoys06-1943.htm, accessed 5 Jan 2016

[7] Royal Air Force Costal Command by John Campbell

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convoy_Faith, accessed 6 Jan 2016

[9] http://www.richardpgibbs.org/2015/04/1943-road-to-algiers.html, accessed 5 Jan 2016

[10] http://www.pandosnco.co.uk/stratheden.html, accessed 6 Jan 2016

[11] The Deolali camp is the source of the slang phrase ‘doolally’ meaning gone mad or eccentric, which comes from the colloquial ‘doolally tap’, describing a man with ‘camp fever’. This saying was borne out of the length of time men remained at Deolali, mainly at the end of the war whilst waiting for their repatriation back to the UK. The encampment was also the setting for the early episodes of the 1970’s sitcom, ‘It Ain’t Half Hot Mum’.

[12] https://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/global-content/press-releases/england/140813_eng_hr2_vj-day-heroes, accessed 18 Jan 2016

[13] On the order of X List 1/43 2 Ech, authority of G.H.Q(1) 33240/20/A.G.4(b) dated 22/8/43

[14] http://www.chinditslongcloth1943.com/pte-frank-holland.html, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[15] http://www.wishartconnections.org/index.php/the-life-times-of-crawford-tam-wishart-1923-2009, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[16] http://www.nam.ac.uk/research/famous-units/south-lancashire-regiment-prince-wales-volunteers

[17] Before the war the 1st Battalion were in India on internal security duty, based at Meerut , north-east of New Delhi, India, where it remained until 1947, a posting broken by two years fighting in Burma in 1943–45.

[18] http://www.wishartconnections.org/index.php/the-life-times-of-crawford-tam-wishart-1923-2009, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[19] http://www.wishartconnections.org/index.php/the-life-times-of-crawford-tam-wishart-1923-2009, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[20] Forgotten Voices of Burma by Julian Thompson

[21] http://www.chindits.info/Thursday/SpecialForce.htm, accessed 5 Jan 2016

[22] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[23] http://www.chindits.info/Thursday/OperationThursday.htm, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[24] Forgotten Voices if Burma by Julian Thompson

[25] Chindit vs Japanese Infantryman: 1943–44 by Jon Diamond

[26] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[27] https://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/global-content/press-releases/england/140813_eng_hr2_vj-day-heroes, accessed 18 Jan 2016

[28] http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/47/a3249047.shtml, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[29] http://chindits.info/Thursday/DeathWingate.htm, accessed 10 Jan 2016

[30] https://chindits.wordpress.com/2011/04/16/the-chindits/, accessed 21 Jan 2016

[31] 77th Brigade were later ordered to capture Mogaung

[32] http://www.chindits.info/Thursday/FinalBattles.htm, accessed 12 Jan 2016

[33] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[34] Jungle Warfare By J. P. Cross

[35] http://ww2talk.com/forums/topic/41430-1st-battalion-kings-liverpool-regt/

[36] Prisoners of Hope by Michael Calvert

[37] http://www.peter.gerrard.clara.net/burma001.htm

[38] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[39] http://www.peter.gerrard.clara.net/burma001.htm, accessed 7 Jan 2016

[40] Forgotten voices of Burma by Julian Thompson.

[41] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[42] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[43] War in the Wilderness: The Chindits in Burma 1943–1944 By Tony Redding

[44] http://www.chindits.info/Awards/DSOScott.htm accessed 18 Jan 2016

[45] http://ww2talk.com/forums/topic/15663-x-lists-service-records/, accessed 12 Jan 2016

[46] http://www.wishartconnections.org/index.php/the-life-times-of-crawford-tam-wishart-1923-2009, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[47] http://www.wiki.fibis.org/index.php?title=POW_Camps_in_India, accessed 20 Jan 2016

[48] http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=286, accessed 7 Jan 2016

[49] http://www.chindits.info/Thursday/FinalBattles.htm, accessed 8 Jan 2016

[50] www.kral.org.uk/

[51] http://www.paradata.org.uk/units/15th-kings-parachute-battalion-0, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[52] http://www.paradata.org.uk/units/15th-kings-parachute-battalion-0, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[53] http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/99/a5550699.shtml, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[54] ‘Transit’, http://ww2talk.com/forums/topic/15663-x-lists-service-records, accessed 12 Jan 2016

[55] http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/47/a3249047.shtml, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[56] http://www.wishartconnections.org/index.php/the-life-times-of-crawford-tam-wishart-1923-2009, accessed 19 Jan 2016

[57] http://british-army-units1945on.co.uk/infantry/king-s-regiment.html, accessed 19 Jan 2016

Sergeant Stephen Donald McFall 3773874

Sergeant Stephen Donald McFall 3773874, of the 77th Indian Infantry (Division - 3rd Indian, Unit - 1st Bn The King's (Liverpool) Regiment) was given a recommendation for a Military Medal on 6th July 1944, for the following actions:

“On 11th June 44 during the clearing of the triangle (COURT HOUSE) area, he displayed courage and coolness and showed a good example as a leader.

“Most men had passed out from sun and heat exhaustion leaving eleven in the Platoon. The eleven were ordered to assault a lone tree position. During the assault considerable enemy fire was encountered which caused three casualties. Sergeant McFall ignored the firing and was one of the first to reach the objective and held it with two others for a quarter of an hour until the remaining eight men rejoined.

“On 18th June, 44, during the clearing of NAUNGKAIKTAW his section was on the right of the line. He again led his section coolly and fearlessly causing casualties on the enemy, and he saved the life of one of his men. "After this action his Section was ordered to patrol beyond the limits of the village and ascertain whether the area was clear for consolidation. He bumped the enemy, drove him out of the bamboo into a Chaung killing two. Relentlessly he pursued the enemy with grenades driving him into the paddy fields where MMGs and other weapons completed his good work.

"Recommended By:

Lieut Colonel H.N.F. Christie

1st Bn The Lancashire Fusiliers

Brigadier J.M.Calvert, DSO

Commander 77 Ind Inf Brigade

"Signed By:

W. Lentaigne, Major General Comd. 3 Ind. Div.

G. Giffard, General C-in-C 11 Army Group

(London Gazette 26.04.45)”